“Lineage as Legacy,” an exhibit of jewelry and metalwork curated and created by BFA and MFA students in the Indiana University School of Art and Design, was aptly named.

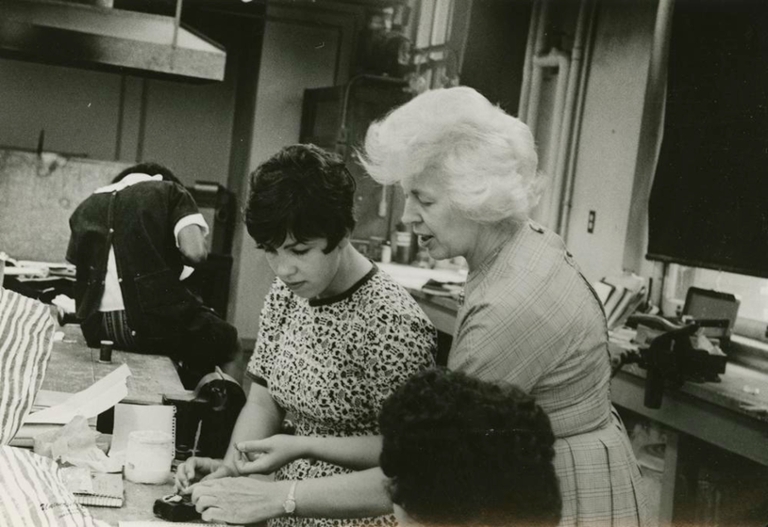

Under the direction of associate professor Nicole Jacquard, students turned a research course on the work of Alma Eikerman, founder of the jewelry-making program at IU, into an exhibit to showcase the importance of Eikerman’s dedication to those she taught through their artwork.

Students began by sifting through Eikerman’s boxes of papers, donated to University Archives. Each student wrote a paper on what they learned about Eikerman, her life, her work and her time at Indiana University from the mix of correspondence, teaching files, paperwork and sketches.

Carrie Schwier, outreach and public services archivist at University Archives, worked with Jacquard, head of jewelry and metalsmithing, and her students to learn about Eikerman's life and work from her records.

“Primary sources have a lot of power to inspire,” Schwier said. “It’s one thing to read an article, but when you’re reading correspondence or looking at sketches, it’s hard not to get excited.”

Eikerman’s life certainly inspirational. Born in 1908 in rural Kansas, Eikerman received a graduate degree in design and painting at Columbia University in New York. It was in New York that she found herself amidst a burgeoning contemporary arts scene. She first took metalsmithing classes at Columbia University, and it would become the focus of her work.

Artistic culture was in the midst of change when Eikerman graduated from Columbia University. Not only was jewelry-making beginning to be used as a way to express individuality rather than status, but the need for occupational therapies for veterans returning from World War II gave way to an increase in artistic programs.

Veterans hospitals offered courses in hands-on arts skills, designed to be therapeutic and to rebuild fine motor skills. These programs fostered demand for specialized fine arts programs at the collegiate level, which was the environment Eikerman entered in 1947 when she was hired to develop the jewelry-making program at IU.

Eikerman spent much of her teaching career as a student herself, taking sabbaticals to Europe to study with Danish metalsmithing masters. She brought back the craft techniques she learned abroad, such as hollowware, and those influences are lasting and evident in both her work and in the work of those she taught.

Not only was Eikerman trailblazing in the world of jewelry-making and metalsmithing, but her status as a female program director in the mid-20th century presented its own challenge. Schwier said it was evident from Eikerman’s papers that she was fighting a wage gap battle as well as an artistic one, paving the way for other women to have similarly prestigious positions at the university.

The more Jacquard’s students learned of Eikerman’s creative work and how her legacy connected to them, the more they felt compelled to share what they had created. According to Jacquard, the program hadn’t done an exhibit at the Ivy Tech John Waldron Arts Center recently, and the class took the opportunity to share both their artwork and their connection to the program’s past.

Jacquard herself is connected to the program's past and Eikerman’s legacy. She studied under two of Eikerman’s students: Fred Brandenburger at Bloomington High School North and IU Distinguished Professor Randy Long. During high school, Jacquard even heard Eikerman speak in a retrospective at IU.

“How fortunate I was to have had a jewelry program in high school,” said Jacquard, whose artistic beginnings led her to a Ph. D. in fine arts and a recent Fulbright award.

Ge Bai, a BFA student in Jacquard’s class, talked about this project’s merging of the past and the present. Bai’s work included designs based on Eikerman’s sketches, but she made it her own with an nontraditional material: eggshells.

“Eggshells for me are the symbol of hope and rebirth,” Bai said. “I think it is very appropriate to use eggshells here not only because it’s the symbol of me, but because of the meaning of rebirth and innovation. Rebirth is very important for art.”

Bai added that she and her fellow students all had different takeaways from Eikerman’s legacy to share as they worked together to create a cohesive exhibit.

Evident from Eikerman’s papers was how important a mentorship relationship with students was, and how that type of relationship fostered the legacy of her teaching. Within the boxes were letters to and from former students, something Jacquard herself found special.

“We tell them once you’re part of a family, you're always part of a family,” Jacquard said of her students. “Hopefully they’ll understand the importance of this institution and the role of a woman in creating this legacy.”

IU professors interested in incorporating primary sources in their course can reach out to University Archives, whose programming includes a workshop on using primary sources, for more information.

“Lineage as Legacy” was on display at the John Waldron Arts Center earlier this summer. Participating artists included BFA students Ge Bai, Angela Caldwell, Ben Cooke-Akaiwa, Kerry Guan, Boxun Hu and Danni Xu; MFA students Shawn Lopez, Nathalie Maiello, Zach Mellman-Carsey, Gabriel Mo, Heather Nuber and Rose Schlemmer; and Jacquard.

Original Source: IU Newsroom