Source: AIGA Eye on Design

Making Public Information Actually Accessible to the Public is the Responsibility of Designers

What good are dense government documents like the Mueller report if they're not designed for public consumption?

Parsing dense government reports that are hundreds of pages in length, set in 12pt Times New Roman, and full of legal jargon and footnotes may be the stuff of a designer’s nightmares. Yet it’s difficult to imagine a clearer example of bureaucratic thinking, or what might be termed an “administrative aesthetic”—a favorite of lawyers, policy makers, and the committees tasked with investigating them. Take the Report on the Investigation Into Russian Interference In The 2016 Presidential Election—or as is more commonly known, “the Mueller report”— released by the Department of Justice in the spring of 2019. The document first arrived to the public as a scanned PDF, impossible to ‘F search’ and heavily redacted. Elected officials on both sides of the political aisle were united in their struggle to read the document in its entirety, creating, according to reporting by Politico, “a giant literacy gap in the country when it comes to the most authoritative examination into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election and whether Trump obstructed that investigation.”

If you could get through it, though, the contents of the Mueller report read like a veritable spy novel. From stolen documents and cyber warfare to the Russian Internet Research Agency’s “active measures,” complete with fake Facebook profiles and group pages created to “provoke and amplify political and social discord in the United States,” the report uncovers threats made against free and fair elections as well as systemic efforts to undermine faith in the U.S. electoral process. But what good is it if information ostensibly generated for public consumption is not designed for public consumption? Just as bad design can wreak havoc—the infamous butterfly ballot from the 2000 election comes to mind—good design can illuminate and inform, aiding citizens in their participation in our democracy.

What good is it if information ostensibly generated for public consumption is not designed for public consumption?

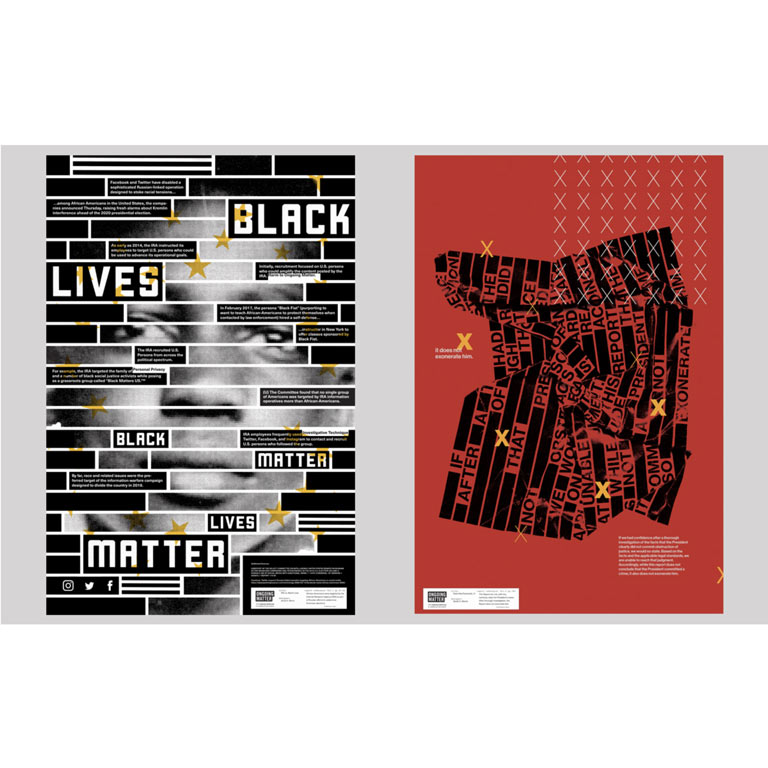

In the summer of 2019, we began meeting virtually with a small group to discuss the Mueller report and our responses to it. The revelations in the report, many of which are shocking and difficult to comprehend, inspired us to develop a series of 37 posters, produced by 14 artists and designers. The result is Ongoing Matter: Democracy, Design, and the Mueller Report, a project that uses design to elevate and compel engagement with information that is buried in citations and pages and pages of text. From a creative perspective, the report provides endless material for exploration. However, the motivating force behind Ongoing Matter—perhaps belied by adherence to detailed design specs and aesthetic considerations—was a collective sense of urgency. From the moment we began brainstorming as a group, we were in complete agreement on one key point: more people need to read the Mueller report.

Pooling the ingenuity and creativity of designers, Ongoing Matter is reminiscent of a wiki. Creatives work collaboratively, dividing up content, breaking information down into digestible pieces, and investigating themes in the text through iteration and feedback, contributing to a larger collection of knowledge-building in the process. Instead of retroactively redesigning the report, artists and designers deploy clever integrations of type and image to call attention to the content. The ongoing body of work is diverse in perspectives and interpretations, yet visually and thematically unified.

But ours is just one method for achieving literacy and awareness. Another approach reimagines government documents as well-designed experiences. Imagine if these reports borrowed data visualization techniques from annual reports (i.e. WarbyParker 2013), or indexing and sectioning from e-books. What if they used digital storytelling or UX/UI web techniques that hook viewers and keep them reading? This is an area in which communication designers could use our skills in service of public access to information, for if government reports are not designed for the public, what is their real purpose or value?

There are numerous examples of reports released recently that could have used a designer’s mind in order to make them understandable to a general public. Just a few examples: the August 2020 116-XX Senate Intelligence Report, a bookend to the Muller report and its exposing Russia’s active interference in U.S. elections, is 1,000 pages of Times New Roman legalese. The 2020 Supreme Court ruling in Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo (No. 20A87) regarding the intersection of COVID restrictions in New York and freedom to worship—a significant case impacting the health and safety of NY residents—was no easier to understand than U.S. federal COVID policy. Finally, the Green New Deal (H. Res. 109), a legislative proposal addressing climate change and environmental protection, is a travesty of rag alignments and text oddly set in stretched ITC Cheltenham Bold and Monotype’s Modern Standard.

This is not to say that typeface choices alone can make these reports more accessible. But synthesizing type, language, organization, hierarchy, and virtual deployment strategies could more effectively design these documents to reach a wide range of audiences in a variety of formats and contexts. We’ve seen examples of this in projects like the New York Times’s interactive Mueller report, which indexed and hyperlinked the text. News organizations—the free press—play an important role in elucidating policies and reports, wading through documents that may require a certain level of expertise to interpret. We’d like to see more of that, in a variety of iterations and experimentations with format, because the more pathways in to these documents that we create, the more accessible they become. And we’d like to see designers—whether in newsrooms, non-profit organizations, government agencies themselves, or through self-initiated projects like ours—be leading the way.

In the era of “fake news,” graphic design must address the gaps between information dissemination and the public’s ability to understand it.

We chose to focus on the Mueller report, but there are countless other examples of how design could and should make large amounts of information accessible and understandable. In the era of “fake news” and rampant disinformation campaigns, graphic design must address the gaps between information dissemination and the public’s ability to understand it. In the absence of clarity, former U.S. Attorney General Bill Barr was able to skew the public’s understanding of the Mueller report’s contents and conclusions when he presented his own summary letter prior to the release of the full report (Graham, 2019). Through his actions, Barr presented a narrative that favored Donald Trump, a central figure in the Mueller investigation, misleading the public in the process.

Access to information is crucial to the public interest in functioning democracies. In the epilogue to his essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Walter Benjamin argues that fascism packages politics up as aesthetic spectacle while simultaneously denying the rights of its citizens. Ideologically opposed to this, Benjamin calls for “the politicization of aesthetics,” in which art is functional and answers to politics. Aesthetics should be responsible for and responsive to the true needs of the people. By contrast, poorly designed government reports, like the Mueller report, ultimately impede the average citizen’s engagement with civic knowledge.

When we began working on Ongoing Matter, we started with the question, “How can we make this 448-page beast easier for the average person to understand?” Now, we are asking more broadly, “How can we address the gaps between the dissemination of information important to the public discourse and the public’s ability to access it?” Our open call for contributions is, in effect, our invitation to other designers to help address these same questions. The call for participation in Ongoing Matter—and to a greater extent democracy—is still open.