f you work in city planning, economic development, or design in Indianapolis long enough, you are almost obligated to say, “We don’t have mountains or oceans but …”, before any discussion. It’s a sort of precursor statement. A setup. One that lets your audience know that you are aware of your order in the world. “We aren’t as great as some places, but we have other good things!”

I hate it.

I think Joseph Cantor did, too.

When I was the director of metropolitan development for the city of Indianapolis between 2012 and 2015, no other topics came up more often than design and architecture. Underneath nearly every discussion was an understanding that—with the notable exception of Columbus—Indiana wasn’t a place with great buildings. It was disheartening for me because I love the state. I was born and raised in Fort Wayne, lived and worked in Indianapolis for years, and my wife and I are now raising our family in Bloomington. I don’t like the idea of talking down about the place where I’ve chosen to live my life. And, after nearly seven years of digging through old archives from 70 years ago, I’m starting to wonder if our design reputation might have turned out differently.

In August 2015, I started working on planning and design at Indiana University. Soon after I began, I was told that the famous modernist architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe had designed a fraternity house at IU Bloomington in the early 1950s. My first response was complete dismissal. I couldn’t imagine that being true.

I had started my career in Chicago and was very aware of Mies, the titan of modern design and architecture who was born in Germany in 1886 and lived until 1969, when he passed away in Chicago. Best known for coining the phrase “less is more,” Mies was a modernist innovator. Edward Windhorst, one of Mies’s biographers that I have gotten to know, put it well: “Mies invented something new. He invented a language for architecture that the structure of a building itself was graceful and beautiful. The structure didn’t need to be covered up.”

Mies lived two architectural lives. His first was in Europe and included designs such as the Barcelona Pavilion, the German entry into the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition, and the Tugendhat House in the Czech Republic, one of the seminal works of modern architecture. His second came after he fled Germany in 1938 to come to the United States to be the chair of the Department of Architecture at what is now known as the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago. During this time, his architectural practice produced projects such as the white-painted steel-and-glass Edith Farnsworth House, the black steel towers of 860–880 Lake Shore Dr., and many of the campus buildings of IIT, including S.R. Crown Hall—all iconic examples of architectural modernism today.

By the early 1950s, he was arguably the world’s most famous architect. And he was working in Bloomington. On a fraternity house.

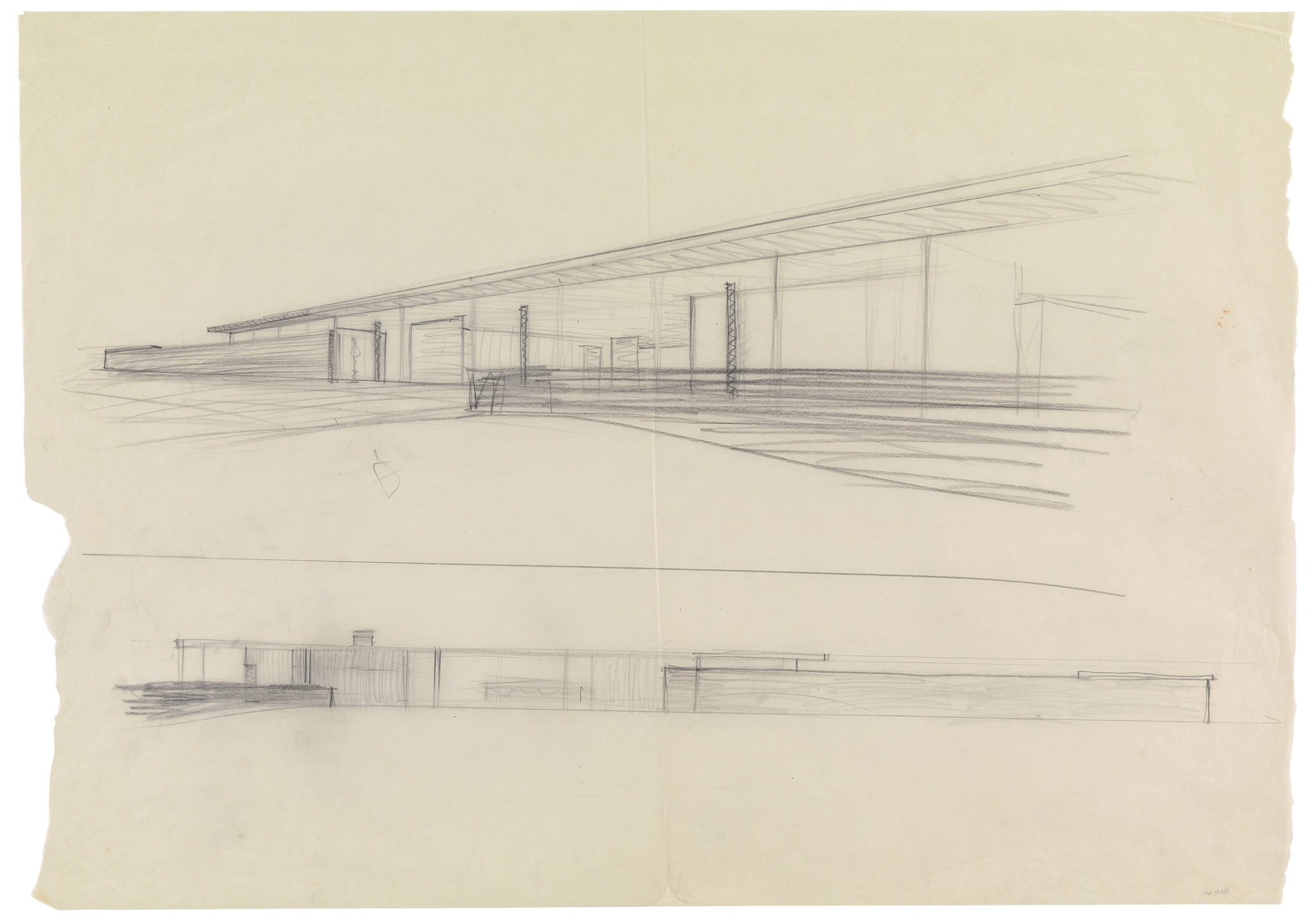

The real estate developer and philanthropist Sidney Eskenazi was a member of that fraternity, Pi Lambda Phi, and recalls how bad the condition of their house was during that time. “You could hear the mice running in the walls,” he says. It had been condemned by the fire marshal. Members of the Pi Lambda Phi Alumni Club decided they were going to build a new house for the boys in Bloomington, and they were going to hire the world’s best designer. Mies and his team were retained, and they worked on the project throughout 1951. In February 1952, the plans were unveiled, and the press called it “the most unusual fraternity house in America”—a two-story steel and all-glass structure. Despite the fanfare, financial troubles ensued and fundraising slowed, and by 1957, the project was dead.

Until 2013, when Eskenazi mentioned that lost bit of history to former president of IU Michael McRobbie. Nobody working at the university had heard of the project. Mies scholars didn’t even know of it. Mies’s own grandson, Dirk Lohan, a distinguished Chicago architect who worked for Mies in the early 1960s, told me, “In all my years of working for Mies and understanding all his projects, I’ve never heard of this building design. But the documents you have uncovered confirm it is a Mies van der Rohe design.”

So why was Mies van der Rohe, world-famous architect, working in Indiana? Over the last seven years I, along with IU faculty member Jon Racek, have been digging in the old papers and archives of the Art Institute of Chicago and New York’s Museum of Modern Art Mies Archive for clues. During that search, we ran into Joseph Cantor.

Born in New York, Joseph Cantor moved to Indianapolis in the early 20th century to become a film distributor in a golden era of movies. He had big dreams for his company, Cantor Amusements. Big enough dreams to cold call the world’s leading architect in August 1945 to ask for his help designing—wait for it—a bowling alley at the corner of Lafayette and Georgetown roads in Indianapolis. Stunningly, Mies said yes.

The bowling alley project never got far, but Cantor had other ideas. Suburban living and the automobile were the future, he thought, and he had his eye on a parcel of land on 38th Street south of the Indiana State Fairgrounds. That parcel was ideal for a new restaurant concept, and Mies was the man to design it. The design for the Cantor Drive-In Restaurant is well-known in Mies scholarship, and he worked on it with Cantor for almost five years. The unique structure, the all-glass exterior—it presaged design elements that can be seen in Mies’s world-renowned works in Chicago and beyond. And he was doing it in Indianapolis.

Cantor was Mies’s most significant private client after World War II, and he even asked the architect to start on a design for a summer home on a parcel of land in Hamilton County. The design envisioned a flat-roofed, all-glass-exterior house of a single level—a massive home of more than 10,000 square feet. His dreams ran into financial realities, and neither of the projects were ever built. But Mies wasn’t done designing in Indy.

Cantor introduced Mies to Harry Berke, an Indianapolis real estate developer who had a similar love of contemporary architecture. In 1950, he employed Mies to design a four-story, stainless-steel office building at the southwest corner of Michigan and Meridian streets downtown. Mies and his team spent countless hours on the project, even developing a full-scale model built to exacting dimensions. Additionally, by 1953, Berke unveiled a 12-story Mies design and detailed model for a new, all-black steel apartment building at the corner of 36th and Meridian streets. Both projects ran into financial trouble and, like all of Mies’s designs in Indianapolis, were never built. They have rarely been discussed in the almost 70 years since.

Of course, the elephant in the room is: Why weren’t they built? The source documents are scant on details, but it appears the tremendous aspirations of the architect hit the financial limits of a local real estate developer. That narrative is surprisingly common. Buildings don’t magically appear. Special ones appear even less. There is always a tension between the forces of design, aspiration, construction, finance, and feasibility.

What would have happened had the Cantor Drive-In Restaurant been built in 1947 in Indy? The Berke apartment building in 1953? In a way, elements of them were built. Look closely at the designs of local office buildings and apartments of the mid century—Mies’s influence is everywhere in structures from that era. Unfortunately, few had the ability to deliver the master architect’s carefully refined buildings, and often the result was what so many dislike about modernism: bland, soulless design.

We now know that Cantor and Berke were ultimately the connections for Mies to the Pi Lambda Phi project in Bloomington in 1950. My hunch is that there were ties between the Indianapolis Jewish community and the strong Jewish contingent at Pi Lambda Phi. Even though Mies’s Indianapolis projects never came to fruition, they led to a design for a white-painted steel-and-glass pavilion that now sits on one of the most beautiful college campuses in America.

Cantor and Berke had big dreams. Maybe we should, too. Despite our downtrodden design reputation, there was an era when Indiana was commissioning the world’s leading architect to build bowling alleys, offices, and fraternity houses. Maybe the next great designer already lives here—excellence doesn’t have to come from afar. What should we aspire to next?

Mies in Indiana, an exhibit curated by Adam Thies and Jon Racek, opens at the Grunwald Gallery of Art in Bloomington on August 26.