Source: The Journal

An artist's process can unfold in a few directions. Some artists make detailed sketches or maquettes before beginning a work, and the result is almost a fait accompli before it's even been started. Sometimes artists might know pretty much where they're headed, but open themselves up to veering off the original plan as they work. And others are more immediate in their approach, responding to ideas, instincts, moods, and environmental factors as they pop up. They likely have a personal visual vocabulary and sensibility, but the art is very much born in the moment.

Malcolm Mobutu Smith is mostly in the latter category.

Working this way allows for the unexpected, the daring, the playful, and the "where did that come from?" kind of art. It's an approach that has served him well in his studio practice.

Smith is an artist and teacher who holds a Master of Fine Arts degree from the prestigious ceramics graduate program at Alfred University in Alfred, NY. Presently, he is an Associate Professor of Ceramic Art at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana. He's also taught classes in Florence, Italy -- which is a lovely job if you can get it!

He was exposed to art as a child -- both parents were artists. His mother studied painting and drawing and his father, sculpture. So he tells me, "I had an awareness of the arts. They pointed the way -- pointed my ship as it were -- in that direction."

Born in Michigan, but mostly reared in suburban Philadelphia, Smith was connected early on to important mentors. At Conestoga High School in Pennsylvania, his ceramics teacher was Paul Bernhardt, who years earlier had taught ceramicist Chris Staley.

When he was only 14, Smith took his first-ever class "outside of high school" with Staley at the Peters Valley School of Crafts in Layton, NJ.

Then in 1988, Smith returned to Peters Valley to work as the studio assistant for Ken Ferguson and other artists, absorbing new techniques and having the chance to exhibit his work in the Peters Valley Gallery. He was "only 16 or 17 years old," he tells me.

After high school, Smith attended the Kansas City Art Institute for two years, where he studied with Ferguson, eventually switching to Penn State for financial reasons, where he studied with...Staley again! I guess the ceramics world is a small one and very interconnected.

In Alfred University's MFA Program, he worked with what he refers to as an "amazing faculty" (Wayne Higby, Val Cushing, John Gill, Andrea Gill, Anne Currier, and Doug Jeck) with whom he "forged great and meaningful connections."

Smith came out of all these experiences ready to share his knowledge. Since then, he has not only taken on full-time, tenure-track college positions, he has also traveled widely, presenting dozens of workshops and lectures. (He taught at Peters Valley in 2019.)

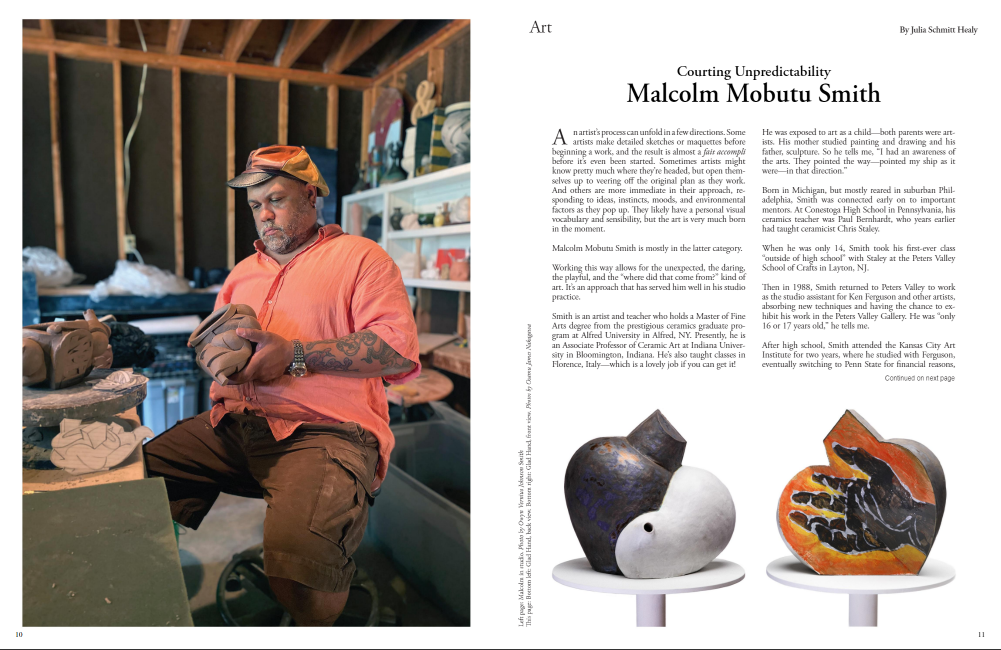

But what of the work? It is usually formed from a wheel-thrown vessel. "I start with that and then I improvise," he says. Since he teaches what might be called classical throwing techniques (meaning that students need to center their clay and pull up a symmetrical pot), he can produce a perfectly beautiful shape that many ceramicists would be happy to leave as is.

Watch one of the many YouTube videos Smith has recorded and you'll see him gently patting and slicing new edges and shapes into the pliant clay. It is still a vessel, but it begins to take on a new personality, as it were.

With a background in numerous contemporary art forms, such as hi--hop music, jazz, breakdancing, and graffiti, Smith puts a fresh spin on what a pot can be because he uses these unusual sources as inspiration.

Wexler Gallery in Philadelphia, which represents his work, notes: "His abstracted forms become locations for invention and the unexpected...operating as signifiers of aesthetic acculturation and identity politics, reflecting back to us our desires and imaginations."

His works are playful, unsymmetrical, wild, pointy, and sharp-edged. Some are squat and bent. Others mimic plant forms. Some have a geometric elegance. Others look like they could have grown out of a tree. Many are not functional and can't actually be used as a cup or vase.

Since Smith has also studied and taught drawing, painting, and printmaking, his constructions and surfaces reflect his interest in two-dimensional disciplines. The pieces are all glazed, not painted, which is amazing because glaze coloration is a lot trickier than paint mixing.

Occasionally, Smith tells me, he'll begin with a hand-built, as opposed to a wheel-thrown, vessel. "I exploit the plastic abilities of clay and see where that leads me." He seems to be always experimenting, always in the moment.

He does not make what we might call "stock pottery." He doesn't have a "line" or catalog of objects for sale. He makes art that happens to be made of clay.

Recently, he's been working on some pieces based on clouds -- clouds that are floating. "They are cups or scoops in which vectors overlap, making them look kind of like they're floating," he says.

In 2022, Smith had a show at the Hunterdon Art Gallery in Clinton, New Jersey. As part of the exhibition, the Roxey Ballet performed outdoors, responding to his work using the art form of dance. The collaboration was a positive way to experiment and added an extra dimension to the exhibit.

Watch the dance performance and learn about the Hunterdon show

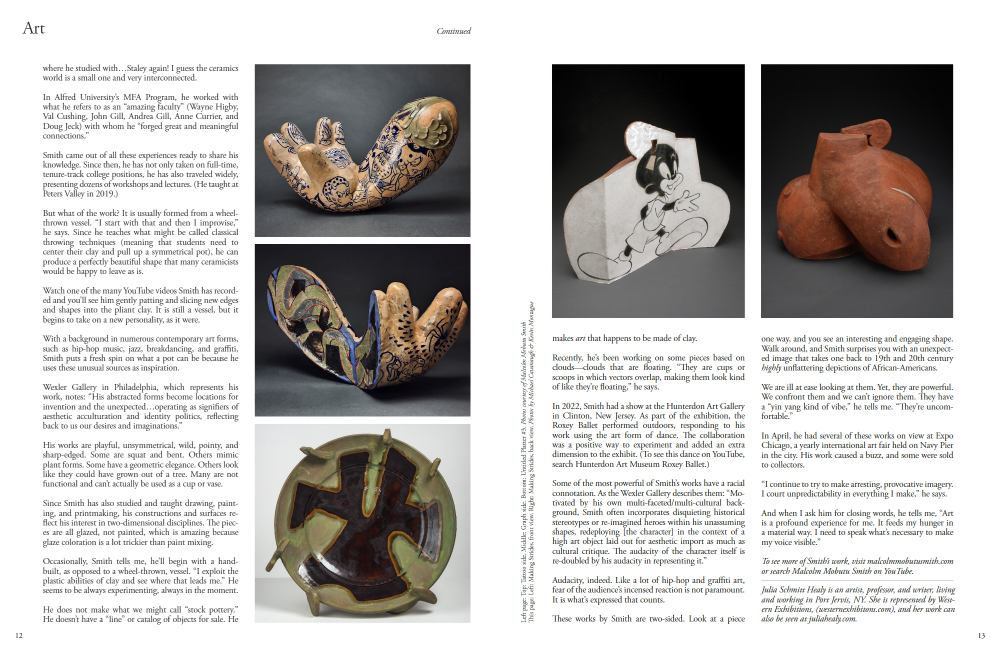

Some of the most powerful of Smith's works have a racial connotation. As the Wexler Gallery describes them: "Motivated by his own multi-faceted/multi-cultural background, Smith often incorporates disquieting historical stereotypes or re-imagined heroes within his unassuming shapes, redeploying [the character] in the context of a high art object laid out for aesthetic import as much as cultural critique. The audacity of the character itself is re-doubled by his audacity in representing it."

Audacity, indeed. Like a lot of hip-hop and graffiti art, fear of the audience's incensed reaction is not paramount. It is what's expressed that counts.

These works by Smith are two-sided. Look at a piece one way, and you see an interesting and engaging shape. Walk around, and Smith surprises you with an unexpected image that takes one back to 19th- and 20th-century highly unflattering depictions of African-Americans.

We are ill at ease looking at them. Yet, they are powerful. We confront them and we can't ignore them. They have a "yin yang kind of vibe," he tells me. "They're uncomfortable."

In April, he had several of these works on view at Expo Chicago, a yearly international art fair held on Navy Pier in the city. His work caused a buzz, and some were sold to collectors.

Read about Smith's work at Expo Chicago

"I continue to try to make arresting, provocative imagery. I court unpredictability in everything I make," he says.

And when I ask him for closing words, he tells me, "Art is a profound experience for me. It feeds my hunger in a material way. I need to speak what's necessary to make my voice visible."

To see more of Smith's work, visit malcolmmobutusmith.com or search Malcolm Mobutu Smith on YouTube.