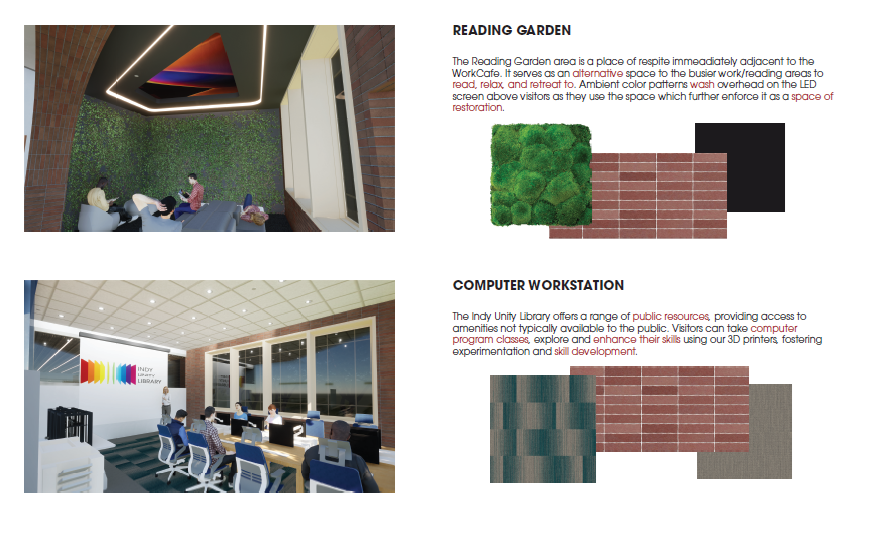

In the library of the future, there’s a shop where you can work on your bike. And a lab where you can try out 3D printing. Or gather in a classroom with others to learn a language.

“I see the library taking on the role of community connection point in the future,” said graduating Interior Design student Ibrahim Al-Mohanna. “There’s no longer the need for a library to be an emporium of physical media.” So for his capstone project, exhibited at the Cook Center on Tuesday, April 23, he reinterpreted the municipal staple in a way that corresponds to contemporary needs.

“I read that libraries serve as the living room of the city,” explained Al-Mohanna, who wants to make sure that living room is hospitable to those of “diverse educational and cultural backgrounds.

Recognized in 2023 as one of five winners nationwide of the Diversity in Design Pipeline Scholarship from Thermador in partnership with the Interior Design Society, Al-Mohanna is attentive to the challenge of designing for a diverse user base. “Libraries are open to all, indiscriminate, they accept everyone,” the senior said. “For so many people, such as those who are unhoused, it’s a safe place they can go and not feel rejected.”

At the turn of the last century, Andrew Carnegie championed the public library as an instrument of self-improvement and funded the construction of more than 2,500 of them across the country. Al-Mohanna’s Indy Unity Library updates the institution for the 21st century. In his purpose-built facility, users of all backgrounds can connect to the kinds of resources that promote skill-building and personal growth for these times. And that, Al-Mohanna argues, strengthens the greater community.

Al-Mohanna’s ability to draw connections between a library’s floorplan and the community as a whole speaks to his interdisciplinary degree program: in addition to his Interior Design major in the Eskenazi School, the IU student has earned a minor in Urban Planning through IU’s O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs.

“In general, there’s a decent amount of overlap,” Al-Mohanna says, “more than people would imagine. Things such as space planning within a building can be comparable to zoning within a city because you still have to, in both cases, consider the effect of spatial relationships based on the way things function. You can also draw a comparison between human circulation inside a space and traffic, and how that needs to be considered and organized within the overall footprints.”

Raised in Noblesville, Indiana, Al-Mohanna became interested in cities and the buildings in them on a trip to Germany and the Netherlands in high school. The tour impressed upon him the power of beautiful architecture. Not only from the street view. Early in his studies, he said, “I realized that I could have more opportunity to affect user experience as an interior designer than in other professions, because people interact with the inside of the building way more than they interact with the outside.”

Al-Mohanna’s passion for the user experience banishes the stubborn trope of the designer as self-absorbed aesthete, detached from the needs of those who will eventually interact with his designs. Al-Mohanna credits his Eskenazi training for his fixation on the end user.

“In virtually every studio project, we’re presented with a fictional client where we need to respond to their specific needs,” said Al-Mohanna. “Listening to the client or the stakeholders is probably the biggest consideration for all designers. At the end of the day, you’re ultimately serving the client or the community that’s receiving the design work.”

A project designing an outpatient employee health clinic presented the opportunity for interaction with real clients, whose feedback informed the iterative process and transformed the final design. Speaking with employees of Cook Medical, a Bloomington employer with whom the Eskenazi interior design program regularly partners, Al-Mohanna and his team learned that health clinic visitors want more privacy from the waiting room when registering at the reception desk. That insight prompted the team to reenvision the clinic's entry.

“My professors’ emphasis on design thinking early on resonated with me,” he said; “it was an approach to design problems from a human-centered approach, emphasizing empathy, collaboration, and iteration. That approach taught me to think more critically about the needs and experiences of users, and to design solutions that are truly meaningful and effective.

“The thing they say early on in the program is, ‘This is not HGTV,’ which happily it is not.”

The program’s substantive rigor manifests in classes such as Design and Culture with Bryan Orthel, which, Al-Mohanna explains, “deals with moral questions, and how to navigate them with design.” The related issue of sustainability is a central pillar in the discipline, and of the program. Learning how to minimize a building’s carbon footprint is one of the designer’s highest priorities: through his projects, Al-Mohanna has been taught design strategies that support sustainable building systems, for heating, cooling, or lighting, for example.

When he graduates this week, Al-Mohanna will be recognized as a member of Phi Beta Kappa and the Dean’s List, a Founder’s Scholar, a recipient of the Opal G. Conrad Scholarship (Eskenazi Interior Design school award), and a former Eskenazi School Student Advisory Board Member. Earlier this year, Al-Mohanna represented IU in the student charrette design competition at the IIDA SHIFT Conference in Dallas.

Having recently passed the NCIDQ IDFX Fundamentals exam, the first of three required for a license in Interior Design, Al-Mohanna soon plans to pursue his M. Arch degree.