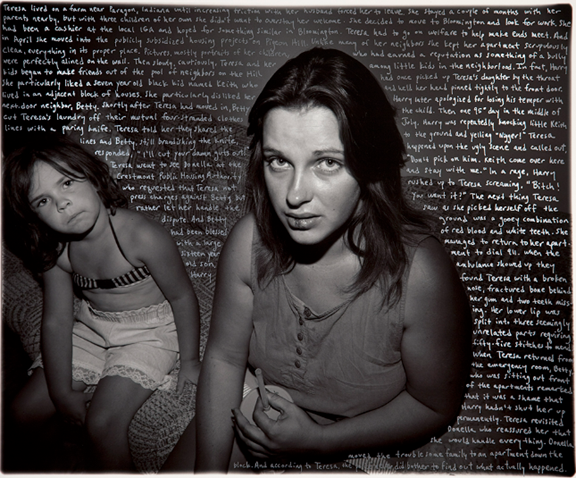

“Throughout his career, photographer Jeffrey A. Wolin has focused on the impact of poverty, war, and trauma on human experience, memory, and hope. His first job as a police photographer influenced his candid approach, as well as his deep respect for human resilience. Wolin combines his love of words with a passion for making photographs, writing the stories of each subject directly on their images. The resulting works fuse his own aesthetic ideas with the voice of the people he so intimately engages.”

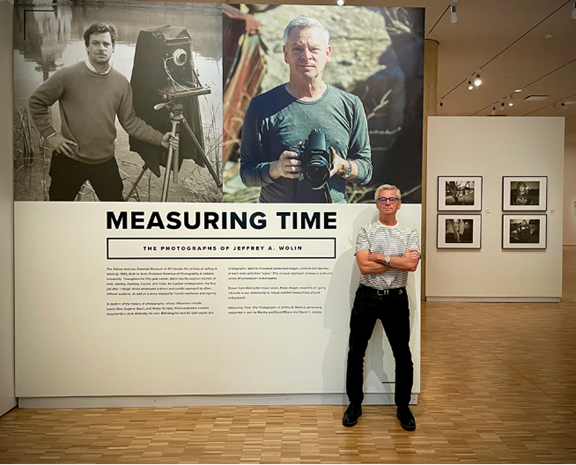

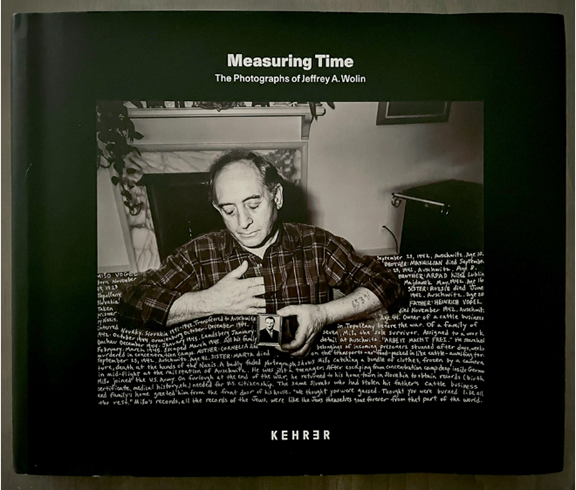

The exhibition opened at the Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University and will run through December 17, 2023, in the Featured Exhibition Gallery.

Jeffrey A. Wolin is a celebrated and influential photographic artist and former longtime head of Indiana University’s photography department. Featuring one hundred works, this retrospective exhibition covers Wolin’s entire career with key selections from all ten of his major series, including his earliest landscapes and portraits of stonecutters, Holocaust survivors, war veterans, and people experiencing homelessness. The sum of Wolin’s creative achievement will be a surprise and inspiration to nearly every viewer. His work is powerful and profoundly humane. Over the years, he has thought deeply about the issues of human history and memory, always attentive to the insights that come from personal storytelling. Best known for his innovative use of image/text combinations, Wolin has explored the living reality of history and the primacy of the personal experience. His work is at once formally inventive and deeply empathetic and sympathetic. Wolin’s pictures provide fresh and powerful insight into the course of time and the complexity of individual lives. Few others, in fact, have explored these issues with anything approaching Wolin’s insight, generosity of spirit, and artistic invention. His work expands our sense of both the art of photography and the poignance and integrity of human existence.

“I have been moved by Jeff’s interest in the people and places that have shaped his life, from his student days in Rochester, New York, and long teaching career in Bloomington, Indiana, to his travels in the south of France and his current home in Chicago. While his works often begin with the local, they embrace universal themes, like family, community, poverty, war, and the environment, that touch us all.” Nanette Esseck Brewer, Lucienne M. Glaubinger Curator of Works on Paper, Eskenazi Museum of Art

“We are excited to present this retrospective exhibition of Jeff Wolin’s work, which celebrates his unique ability to capture the humanity of his subjects. The exhibition allows us to demonstrate our commitment to collecting and exhibiting photographic works of art, as well as dedication to providing learning opportunities to IU students through direct engagement with Wolin’s work. We look forward to connecting with our community via Wolin’s powerful, empathetic, and compassionate storytelling. I extend my heartfelt thanks to Martha and David Moore for their help in making this exhibition possible,” said David A. Brenneman, Wilma E. Kelley Director, Eskenazi Museum of Art. Measuring Time: The Photographs of Jeffrey A. Wolin is supported in part by Martha and David Moore.

It is curated by Nanette Esseck Brewer, Lucienne M. Glaubinger Curator of Works on Paper, Eskenazi Museum of Art, and Keith F. Davis, independent photographic historian and former Senior Curator of Photography, Nelson-Atkins Museum, Kansas City.

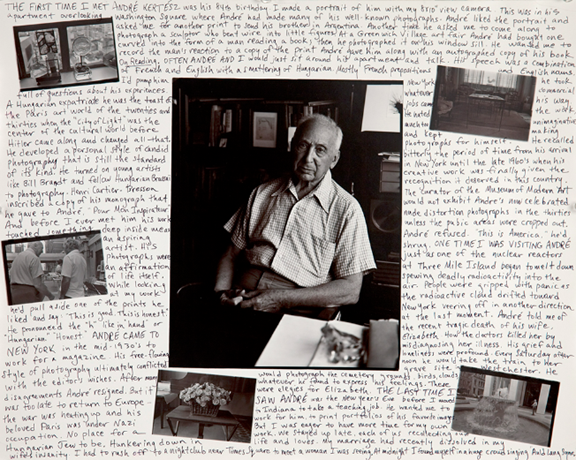

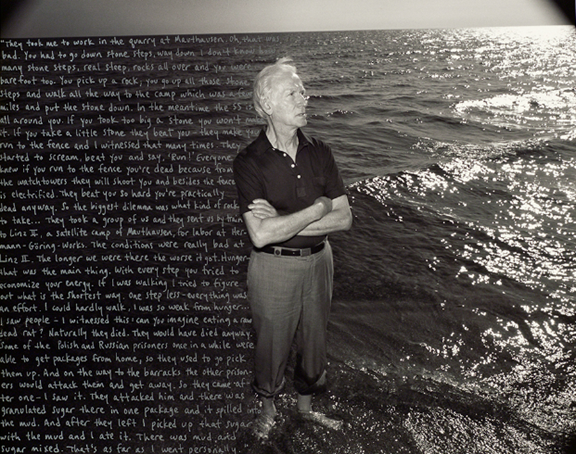

Written in Memory: Portraits of the Holocaust, 1988, 1991–95

In 1988, I made a photograph with an inscribed text of Mišo Vogel, an Auschwitz survivor living in Indiana. For the narrative, I used notes I had taken while talking with him during our portrait session. I wanted to show his tattoo, which is in and of itself a powerful visual statement about the brutality of the German war against the Jews. I also asked him to hold a photograph of his father who died in Auschwitz. This image acted as a window, and Mišo closed his eyes, put his hand over his heart, and was, for a moment, transported back to a painful time in his past.During my year off from teaching as a Guggenheim Fellow (1991–92), I decided to build a series of images around the photograph of Mišo. I began each session by videotaping each survivor’s story prior to making portraits with my still camera. Instead of rewriting accounts of the survivors in my own words, I began to excerpt whole chunks of the testimonies verbatim, letting the individuals speak for themselves. I tried to keep the “flavor” of the European accents, which often reminded me of my own grandparents, who emigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe at the turn of the twentieth century. I looked for small, intimate details in the survivors’ narratives rather than grander, more generic experiences, or statistical data, and aimed to match these with visual elements in their environments that resonated with their stories of survival.

Someone who did not directly experience the Holocaust cannot truly understand the depths of horror that Jews in Europe endured at the hands of the Nazis. Nevertheless, it is my hope that by opening a window to an individual through their image and accompanying story, an audience will empathize with the survivors.

Faced with the loss of home and family and confronting a future in a strange land with a new language and new customs, many survivors learned to live with their pain. Most were able to move their lives forward, deciding that life is too short and precious to be consumed with hatred and remorse. This work is a testament to the strength of the individual and to the resourcefulness and resiliency of Holocaust survivors who have an important lesson in humanity to teach us all.

Jeffrey A. Wolin is the Ruth N. Halls Professor Emeritus of Photography and founder of the Center for Integrative Photographic Studies at IU Eskenazi School of Art, Architecture + Design, where he served as director from 1994 to 2002. During his 35-year career at IU, Wolin taught hundreds of students who went on to successful careers in the arts and education, while creating and exhibiting an incredible body of photographic work. Wolin’s photographs have been exhibited in more than 100 exhibitions in the United States and Europe, including solo shows at the Art Institute of Chicago, International Center of Photography in New York, George Eastman Museum in Rochester, and the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, and group exhibitions at MoMA, Whitney Museum of American Art, Houston Museum of Fine Arts, and LA County Museum of Art. His work is included in more than 40 major museum collections in the United States and Europe, and six monographs of his work have been published. He is also the recipient of two Visual Artist Fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and a Guggenheim Fellowship.

The Eskenazi Museum of Art is also home to the Wolin Archive, which serves as an important teaching resource in the museum’s long-standing program of studying, exhibiting, and publishing its collection of more than 22,000 prints, drawings, and photographs collection. The museum’s Center for Prints, Drawings, and Photographs features the Martha and David Moore Study Room, which is equipped with high-quality zoom cameras that allows students and the public to engage with original works of art, as well as access to distance-learning technology.

About the IU Eskenazi Museum of Art

Since its establishment in 1941, the Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art has grown from a small university teaching collection into one of the most significant university art collections in the United States. A preeminent teaching museum on the Indiana University campus, its internationally acclaimed collection includes more than 45,000 objects representing nearly every art-producing culture throughout history from around the world.

The Eskenazi Museum of Art recently completed a $30 million renovation of its acclaimed I. M. Pei designed building. The newly renovated museum is an enhanced teaching resource for Indiana University and southern Indiana. The museum is dedicated to engaging students, faculty, artists, scholars, alumni, and the wider public through the cultivation of new ideas and scholarship.

Interview With Jeffrey Wolin

By Anna Powell Teeter

What kinds of changes have taken place in your work since you began teaching?

When I came to IU thirty-five years ago, I had just left the George Eastman House where I was a photographer and served as Head of Photographic Services. It was an awesome job—I supervised a small staff and volunteer interns from universities around the country. I had access to the archives so I could see the world’s greatest collection of photography. For example, the Eugene Atget photographs they had were not just a random selection, they were ones that Man Ray bought from Eugene Atget and that he thought were his best and most surreal images. So that’s what I grew up loving about Atget—it was Man Ray’s personal selection.

Another thing about that experience was it was sort of the end of the modern era of photography, the formalist era, where photographs were really judged not on their context or content, but strictly on their visual appearance. So the formal value, what makes a photograph a photograph, isn’t the same exact thing by any means as what makes a good painting. It’s not just a picture, it’s made by a machine; it uses light; it employs film. So what makes a photograph a photograph in that sense of the process but also how it looked as a picture, all of that were the formal components of photography.

The modernist approach to photography, which started with Stieglitz, Weston, Moholy-Nagy, Man Ray, etc. came to fruition around World War II. By the time I was in school, it was the only approach that was sort of available to graduate students. Our heroes were people like Diane Arbus, and Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand who are great artists, great photographers. But when the critics were talking about their work they were talking about their formal qualities more so than their content, which looking back on it is crazy. I mean, so much of Arbus is what she’s photographing and how she’s photographing it. For me, whether I bought into it or not, it was the only show in town and when I came to Indiana University to teach, I had recently completed my thesis work at RIT and my thesis was a book. I had a wall show too, but my actual thesis was a book. And I made photographs in the style of Eugene Atget using Printing- Out Paper (P.O.P.) toned in gold, and the Eastman House had all of the old manuals so I could figure out how to do the old photographic processes and I had access to the technicians at Kodak to figure stuff out. By the time I left Rochester, Kodak would refer people to me if they wanted to know how to process their Studio Proof paper which was P.O.P.

I loved the old processes; I loved photography and the history of photography and I was working with big view cameras and I was writing, but I kept everything separate. The writing was on one page, and then a photograph, and another photograph, in visual sequences. But there wasn’t a lot of precedent for that. The Eastman House had as good a library of photographic books as anywhere in the world, and still does, but there wasn’t a lot to look at along those lines. When I was in grad school I studied old illustrated books and illuminated manuscripts—I got a lot of inspiration from them, but there wasn’t a lot of work combining photographs with words directly on them. People were making photographic books of course, but kept everything separate.

So I came to IU and I continued my work. My first major project here was a series of photographs taken over a three or four year period of time exploring the limestone industry and culture. I got permission to photograph in a mill that was active during the week but inactive on the weekends. I would go in and photograph when no one was around—there was such beautiful light and everything was covered with a thick layer of dust. From there I started photographing quarries, and then active mills and active quarries. I connected with Scott Sanders who is a terrific writer here. He had been begun writing about what he was seeing out in the quarries and mills. His vision was quite similar to mine—his in words and mine in pictures, and we eventually did a book together, that was published 30 years ago, called Stone Country. That book had his stories and my photographs. (By the way, we are working together again on a revised edition of the book.)

When the book came out I thought, I’m a storyteller too. I like stories. That’s why I went into photography and continued my writing for a long time, and also studied book arts. I felt like something was missing from the work I was doing. We had an exhibition at around this same time at the Fine Arts Gallery, now the Grunwald Gallery, of folk artists from the South. It was an exhibition of people who are now very well known but I had never heard of any of them at that time. Now we know that these were great artists—Sister Gertrude Morgan, Howard Finster, and some others, and it blew me away. It was their narrative approach to their subject but also, and more importantly, the way they wrote words directly on their paintings. Some of it was visionary stuff, like their dreams. Sister Gertrude Morgan wrote about her marriage to Jesus. Nuns are married to Jesus in a sense, but she meant it more romantically than that. I really loved the look of the writing and the paintings. It reminded me of illustrated books and illuminated manuscripts, but it was different.

Around that time I became aware of the work of Frida Kahlo who also employed writing with her paintings. She was looking at folk art from Mexico and the retablo tradition, and that really spoke to me. So that was it—one day I just sat down—this was in 1985, right when Stone Country came out, and I had a photograph, a portrait that I had made of my father. It had a lot of white space around it. I photographed him from a low angle and the sky behind him was light and I made a 16×20” print and I just started using that white space, writing specific memories from my childhood about my father and my relationship to him. It was an homage kind of thing. It felt really good.

I started thinking about how else I could refer to my personal experiences, I wasn’t that old or anything, but I searched for experiences that are universal. Maybe I focused a little bit more on the painful stuff because in some ways that’s what you remember the most, the difficult memories. So it became a series and I made more and more of these autobiographical photo/texts.

In the ‘70s and ‘80s, the time that I was coming into my own in the art world, the modernist approach was under attack by post-modernism and that meant a lot of things. Feminism was a part of this movement, as was narrative art. All of a sudden it was okay to use text in your visual art; ethnicity was okay to address. It just opened the art world to a much broader, more inclusive, more dynamic approach than what painting and photography and all the other media in the art world had looked like. Photography is a little different than other media, too, because as post-modernism developed, it relied a lot on photography—it was a big part of postmodernism.

Photography was becoming a major part of the art world in a way it had not been before. When I was starting out, photography was a bastard art but that began changing as post-modernism was shoving aside modernism and changing the art world.

It really allowed me to become the kind of artist I wanted to be.

My career had been fine—I was having some good shows, but when I started writing on the pictures I got a totally different response from the art world. Before then I had applied for NEA Visual Artist Fellowships. They were intensely competitive—only 2% of applicants would get them. I applied in the past and hadn’t received one. But when I applied with the photo/text series I got 2 NEA grants within 4 years, wrapped around a Guggenheim Fellowship. The Museum of Modern Art Began to purchase some of my photo/text images, as did other museums.

I began to be included in shows with photographers and other artists using text. My work was in an exhibition at the Chicago Cultural Center called “Urgent Messages.” Howard Finster and Gertrude Morgan were included—so these wonderful artists who had inspired me were in this show and that felt great.

So that is how my work changed after I came to teach—I started combining images and text. I love teaching; I love the enterprise; I love working with my students. When they do well I couldn’t be prouder and happier. But if I’m not doing my work, and making new discoveries for me, if I’m not pushing myself, if I’m not learning new things about photography and about my own work and what it means to be an artist, I can’t be a good teacher. That’s why IU was such a good place for me—it’s a research university. There’s money for your research; they’ll set your studio up; get you the equipment you need; encourage you to travel. As long as you succeed they will help you get to the next level. That is something I have really loved about being here.

The reason I came here was because this was already a well-established art school and photography program. Henry Holmes Smith was famous and his students were great: Jerry Uelsmann, Betty Hahn, Jack Welpott, I knew their work. They were really important photographers.

Has your philosophy of art making and teaching remained consistent or has it evolved as a result of changes in your work/shifts in the art world?

I definitely have changed, maybe just from experience and the passing of time. When I came here I had just two years of teaching experience as an adjunct at the University of Rochester and at RIT, but that was the extent of my teaching.

I did love working with students, of all ages. I knew I enjoyed the process of sharing my love of photography and the creative process with people. When I came here the undergraduate program was solid. They were great people. I am still in touch with many of them and they have gone on to have excellent careers mostly in the arts.

The graduate program was somewhat in shambles. When Henry Holmes Smith left, he was embittered for a variety of reasons. The graduate students had been sort of left to fend for themselves. When I first got to IU, I found the grads to be talented photographers but their work ethic wasn’t strong. There weren’t many demands

placed on them. I don’t know why this was. So when I was 29, I was teaching the grad students, and some of them were my age or older. That was a difficult situation. I was more advanced than they were; I had my MFA degree; I had been teaching; I had work in exhibitions and publications. I knew a fair amount about photography and felt I could help them but I lacked teaching skills at that level.

I was a lot harder then, I think, tougher. But I realized that approach wasn’t working. If you’re a teacher you can totally demolish someone because students look up to you—you’re their mentor, someone who has succeeded in the field and they’re looking to you for guidance. But I found that being harsh just didn’t work. It didn’t get the results. I realized that if you have something difficult to say to someone in a group critique, don’t say it in the critique. I would take notes, and then I would meet with students individually and talk with them and tell them what was on my mind. That became my style pedagogically—if you have something harsh to say to somebody, don’t do it in front of a group. It’s not going to be effective and it’s just not the best way to do it. You still have to be honest and tough, but you don’t have to embarrass somebody to make a point. That is what I learned over time.

What about culture, the art/design world, or your personal experience is responsible for shaping the philosophy that motivates your practice and in turn your teaching?

One of the things that motivates my teaching and my work is really experiencing the world. In modernism painting was about putting paint on a canvas. It wasn’t about interpreting experience of the world. The great Garry Winogrand is quoted as saying, “I photograph to see what the world looks like in photographs.” It’s a tautology. And it’s the definition of modernist photography. There’s some truth to it—we are fascinated by our medium of choice, of course. But if we don’t have something to say, then who is going to look at our work for more than a minute?

Henri Cartier-Bresson is one of the greatest imagemakers in the history of Photography—his photographs are sublime. And they’re vacuous, they’re empty of feeling. His mentor, André Kertész (he was my mentor too!) is also a great imagemaker, but Cartier-Bresson framed things better than anyone. Nevertheless, Kertész had heart; he had soul; he had passion. And his images are sublime in a different way. They teach us something fundamental about life, about the world, about our soul, about why we’re here in a way that nothing Cartier-Bresson ever did could teach us, in my opinion.

What I learned over the years, is whether you’re a writer, a photographer, a painter, a musician, any creative field that you’re in whatsoever, that really what matters is your relationship to the world, to other people, to love. Great art is experiential, psychological and has universality. I think anyone who really looks at Van Gogh gets it—the pain, the beauty, the cosmic.

What matters to me is connecting with a broad swath of people. I certainly want to be respected as a photographer by my field. The peer-reviewed awards, solo exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago, International Center of Photography, group shows at the Whitney, MoMA, etc., my work included in major museums across the country. I’m accepted by my peers but I want to communicate beyond the art world.

What other artists of note seem to share a similar point of view?

I’ve been strongly influenced by many photographers, My favorites are Kertész, Winogrand, Atget. I love so many photographers’ work. Walker Evans. I am influenced by literature as well, I’m an enormous Kurt Vonnegut fan. He would call himself a humanist writer and that’s the kind of photographer I want to be, relating to human experience. I think what I share with him is that I am kind of an outsider in the art world in the sense that most people that love art, they’re drawing by the time they’re four. Their parents are sending them to art classes. I wanted to be a writer. Vonnegut didn’t know what he wanted to do and then he went to the war and came back and did science writing and advertising and whatever else until he started writing science fiction and found his voice. So he was a bit of an outsider in the literary world, but he’s my favorite writer.

I was a literature major so we had to read lots of stuff, I love Chaucer, Faulkner, William Carlos Williams, Ursula Leguin—there are so many great writers.

Film has also been a really important influence because it’s narrative and visual. Truffaut, Fellini, I could watch those films all day. Now is such a golden age for documentary and narrative filmmaking. There’s so much great stuff out there. I thought the movie, Boyhood, was one of the best things I’ve ever seen, in any medium. It was so much about photography and its relationship to the passage of time. It’s a beautiful movie. I’d say in terms of my influences, so many photographers, so many writers, and filmmakers, I like lots of things but those have had the most impact on me. I’ve tried to encourage students to be more educated by seeing films, by reading, by educating themselves outside of just their field.

How is this point of view distinct from other prevalent models? What broad cultural, social, or political ideas does this affirm or deny?

I try to encourage my students to educate themselves liberally. Growing up, I wanted to read Plato and Chaucer and Shakespeare and to look at paintings and be a part of a larger discourse of culture. I really respect people who can speak across a lot of different fields. If anything I really try to encourage my students to educate themselves, learn a foreign language, travel, read, go to the movies, go to museums. My best teachers, that’s what they encouraged me to do so I’m just passing that along.

I had this fabulous teacher in college, Karl Kopp, who really influenced me. That’s part of college, to find someone who you respect who believes in you. This guy taught modern and contemporary American literature. He had gone to Yale as an undergraduate and he played basketball. Karl was funny and irreverent and he turned me onto

a lot of contemporary American literature. I took his class for a year—classes at Kenyon were a year long—and I gravitated towards him and we would have long conversations. And then my senior year I asked him if we could do an independent study, I really wanted to study contemporary American literature with him. I was a big fan of Ken Kesey and Kerouac and the whole beat movement. He’d had some interaction with them when he was in grad school at Berkeley and brought Allen Ginsburg and Gary Snyder to do readings at Kenyon. (I did a portrait of Gary Snyder during his visit—my first celebrity portrait.)

Karl had a profound influence on me. He was a poet and at the time Kenyon had a printing press and we learned how to do typography and run a Chandler & Price press and all that, but we sort of taught ourselves. We’d order type and print books. So I did a book of his poetry then and we stayed friends for years until we lost touch. He was very spiritual, told me about Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, Russian mystics. I don’t believe in religion at all but I believe in the sense of mystery and spirituality, and he turned me onto these great thinkers. Gurdjieff is really interesting. He wrote a book called Meetings With Remarkable Men. Basically the idea was, that to educate yourself, you have to figure out what you need to learn, and you have to know how to go find that information and find the people and the places where you can learn these things. Frank Lloyd Wright was an admirer of Gurdjieff. Alvin Langdon Coburn, a photographer who I had researched when I worked at the Eastman House, was deeply spiritual. He was also an admirer of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky.

Karl turned me onto all that stuff and the whole idea of how spirituality and the art world connect. So we stayed in touch for a long time, this is before the Internet and email, so we would communicate by letter or phone but then we lost touch. Then one day I thought about Karl and I Googled him and his obituary turned up—he had just died the day before. What are the odds? Make of it what you will but for me that was Karl reaching out to me one more time. He was a really important teacher. I used to think that the smartest person is the one who read the most books, and that’s how you learn about the world. I don’t think that now but I think it’s still an important part of it. So educate yourself: learn, read, travel, visit museums, see films experience the world.